Each of the following species grow and flower each year in a ‘cosy’ shade house in my back garden in suburban Melbourne. My definition of a ‘cosy’ shade house is one with a fibreglass roof, shade cloth walls and protection from cold westerly winds in winter. I should point out that frosts are infrequent in my suburb ( North Balwyn) and that my plants are seldom exposed to temperatures approaching freezing point. The six species that I describe below are certainly not rare but they are less commonly encountered than other cool-growing species such as Coelogyne cristata, Osmoglossum pulchellum and Masdevallia veitchiana.

Ada aurantiaca. The genus Ada contains about 15 species, many of them recently transferred from the genus Brassia. All are native to the mountains of Colombia, Ecuador or Peru, where they grow as epiphytes. Ada aurantiaca is by far the most commonly grown species in the genus. Its pseudo-bulbs are about 100 mm tall and its dark green, erect leaves add another 300 mm to the overall height. The inflorescences, each about 300 mm long, bear 10-15 bright orange or red, tubular flowers, and provide a wonderful burst of colour in late winter or spring. In my experience the plant needs to fill its pot before it flowers. In nature, the tubular flowers are pollinated by the probing tongues of humming birds in their search for nectar.

Ada aurantiaca should be potted in a mix of pine bark and Sphagnum moss, the latter making it easier to keep the compost moist. My plant grows happily beside masdevallias in a shade house fitted with automatic misters controlled by a humidistat. Although the species needs less water in winter, its mix should never be allowed to become completely dry.

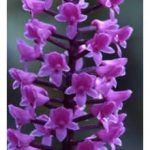

Arpophyllum spicatum is one of about five species in the genus Arpophyllum, all of them being found in or between Mexico and Venezuela, usually at intermediate to high elevations. The species are characterised by long, rigid, strap-like leaves on slender, cylindrical pseudo-bulbs and seem well suited to withstand the fierce winds of their mountain habitats.

The combined length of each pseudo-bulb and its solitary leaf on my plant of A. spicatum is about 600 mm, although it may reach 1.2 m according to some books. The terminal inflorescence bears dozens of small, crowded rose-pink flowers, each held with its lip uppermost. The buds open in late autumn or early winter and the flowers then last for several weeks. The RHS Manual of Orchids (Ed. J. Stewart, 1995) notes that plants will flower only when extremely pot-bound, which agrees with my observation that plants need to be grown into mature specimens. My plant is seldom re-potted or divided, being left for about five years before these operations are carried out. It is hung at the edge of the shade house, where it receives maximum light and air movement.

Other arpophyllum species seen occasionally in Melbourne are A. alpinum and A. giganteum. I imagine from its name that the former would also grow under the same conditions (as for A. spicatum) but I have never grown either species.

Dendrobium moniliforme is native to Japan, Korea and Taiwan and is said to grow further north in the world (and therefore to withstand more cold) than any other dendrobium species. I’ve read that it’s usual to fit straw ‘bonnets’ to the tree trunks on which it is cultivated in Japanese gardens to prevent snow lodging among its leafless canes during winter. In nature the plants are found on both rocks and trees, where their canes grow in dense clusters. The flowers, some 20-40 mm across, appear in spring on the older, leafless canes. The canes vary from 100 mm to 400 mm in length and the pretty flowers, borne singly or in pairs, are either white or pink. D. moniliforme is a member of section Dendrobium, along with other so-called ‘soft-cane’ dendrobiums such as D. nobile, D. wardianum and D. loddigesii. Various variegated-leaf forms exist, many of them being highly prized in Japan. I have two of them but find that they grow and flower poorly, compared with my unvariegated, white-flowered form. This has canes about 150 mm tall and is grown with my other soft-cane dendrobiums in a position in the shade house where it receives full winter sunlight.

Being a dwarf grower, my clone is grown in a 100 mm plastic pot, using my usual dendrobium mix of pine bark and river pebbles (4:1). It is watered and fertilised in the same way as my other dendrobiums between spring and autumn but is kept quite dry during winter and not fertilised at all then. For good flowering, it needs a cold winter, so do not keep it in a heated glasshouse during the dormant season. Some clones produce keikis readily and these are often offered for sale.

Oncidium enderianum is just one of a large number of oncidium species (and hybrids) that can be grown in a shade house in Melbourne. However, by no means can all 400-odd species in the genus be grown without winter warmth. But in general most members of the CrispaandSynsepala (Varicosa) sections are suitable for shade house cultivation. The former contains species such as O. crispum, O. forbesii, O. enderianum and O. marshallianum, while O. varicosum, O. flexuosum and O. spilopterum are members of the latter section; all appear occasionally on our show benches when they flower in autumn. I grow many of these species but have chosen O. enderianum because it often flowers better for me than the other species.

Oncidium enderianum is said to be the most widespread of those species in section Crispa, being found in a number of Brazilian mountain habitats, including the Organ Mountains (at about 1000 m altitude) near Rio de Janeiro. Its pseudo-bulbs are said to grow to 75 mm tall, and its twin leaves to 300 mm, although those of my plants don’t quite reach these limits. Its inflorescence reaches to 300-450 mm and carries up to 16 blooms, each about 40 mm across.

The above oncidiums seem to grow best for me when grown in hanging baskets using coarse pine bark as the potting medium, so that their roots never remain wet for long after watering or fertilising. They should be watered only when they are in active growth, that is, when their roots have active tips. After the plants finish flowering in late autumn, the tips of their roots seal over with a white layer of velamen, and they should not be watered again until new green root tips appear again in spring. If the foliage or bulbs begin to shrivel during winter, they may be misted but resist the temptation to water these oncidiums in the depths of winter. Once new growth begins, the plants should be watered and fertilised regularly, which helps to build up the big pseudo-bulbs needed for good flower production.

The flower spikes usually emerge from the developing new growths in early summer but they mature very slowly, over a period of several months, before the flowers open, usually in late autumn. They last in good condition for about a month. Watch out for caterpillars during development of the flower spikes – they can destroy an inflorescence in a single night, so apply some Carbaryl® dust occasionally. Aphids usually don’t put in an appearance until the individual buds begin to develop in early autumn.

Not all oncidiums respond to the above treatment, some needing regular watering throughout the year. Oncidium ornithorhynchum can also be grown outdoors in Melbourne, but it needs to be kept moist most of the time. Obviously less water will be needed during the winter months but it should never be allowed to dry out completely.

Pholidota chinensis is one of about 30 species in the genus Pholidota, which is related to the genus Coelogyne. Pholidotas occur throughout Asia, from India and Sri Lanka in the west to China in the east. Most require intermediate conditions but Pholidota chinensis will grow and flower quite well in a cosy shade-house. Each pseudo-bulb bears two leaves. The inflorescences emerge from the centre of the new growths in spring, soon becoming pendulous. They are said to bear up to 20 flowers, although 5-6 is more usual for plants grown without heat in Melbourne. The small flowers have greenish yellow petals and sepals and a white lip. They open more widely than the flowers of other common pholidota species, such as P. imbricata.

Pholidota chinensis has such a compact plant habit that a specimen plant can be accommodated quite happily in a 150 mm squat pot. A pine bark compost (5-10 mm) gives good results if the plant is watered and fertilised frequently during its season of growth and allowed a dry rest during winter. The pot should be suspended using a pot hanger at flowering time (December), so that the inflorescences can dangle freely. This species can also be grown in a heated glasshouse, although it then flowers several months earlier. In my experience, plants grown in a cosy shade house flower more prolifically than those grown with heat. Possibly the greater temperature change experienced by those plants grown under unheated conditions promotes flowering.

Pleurothallis truncata . The genus Pleurothallis, which is endemic to Central and South America, comprises at least 1000 species, perhaps as many as 2000 species, some of them still to be discovered and named. Many have small, inconspicuous flowers but some are real ‘jungle gems’, despite the relatively small size of their flowers.

Pleurothallis truncata is a plant of medium size for the genus, standing about 200 mm tall. The pointed leaves, each about 100 mm long, are supported on wiry but sturdy stems averaging 150 mm tall. In common with many other species in the genus, it produces its flowers from the junction of the leaf and its stem. Usually there is a single inflorescence per leaf but well grown plants have two. These support two rows of tiny, bright orange globular flowers, no more than 1-2 mm across, each like a miniature tulip. Inflorescences on well-grown plants carry about 20 flowers. The attractiveness of this species is mainly due to the brilliance of the colour and the cute way the flowers lie opposite each other in two rows on the leaf. Some of my orchid friends have seen it growing in giant masses beside paths in cloud forests in the Andes of Ecuador, which must have been a marvellous sight.

Many Pleurothallis species, including the above, can be grown in a cosy shade-house in frost-free areas. I have two plants of P. truncata, one grown in my heated glasshouse and the other in a shade house together with my masdevallias. There is little to choose between the two, apart from the earlier flowering of the plant grown in the glasshouse. Both plants are currently planted in a mix of fine pine bark and Sphagnum moss but over the years I have used a variety of potting mixes for pleurothallis species without finding any one markedly superior to the others. My plants are never allowed to become totally dry, and they are misted frequently in hot weather. Occasionally Pleurothallis truncata produces keikis from the junction of the leaf and its stem. After these keikis have developed roots they can be carefully removed and transplanted into moss. They usually reach flowering size within two or three years.